Introduction

This project discusses the reproductive health and agency of women in the Central African Republic (C.A.R.) amongst factors of displacement, insecurity, and war. Using the map of a woman’s reproductive body as my outline, starting with lactation and then the womb and sexual health, I trace geopolitical and epidemiological histories through not just everyone’s first home, but within the bodies of those who first experience disenfranchisement. Pulling from family history, personal experiences in C.A.R., and a reproductive justice framework, I aim to shed light on the experiences of real people beyond WHO statistics and MSF articles.

How do Central African women run their homes, work jobs, plan their families, give birth to their babies, and find shelter in a country where one quarter of the population is displaced and multiple empires gamble for leadership? How do scientific and news media articles clarify and re-tangle long-standing narratives that were once deemed useful or even necessary? And what comes of it after all this disruption of dogma and forced empathy? Are structures shifted, beyond the level of the individual?

Through the visual medium of a website, I hope these questions can begin to be answered, and the reproductive injustices women face worldwide can be viewed through the embodied and collective framework practiced here.

A Primer on C.A.R

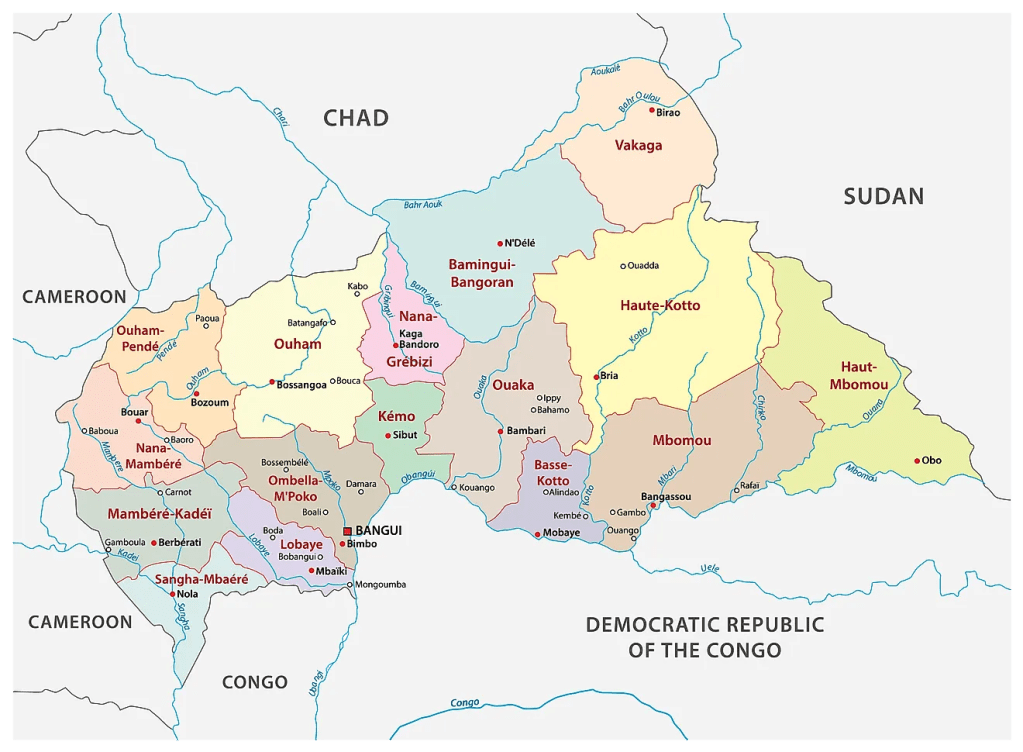

The Central African Republic rests along the equator in the dead center of the African Continent. To its North and East lie Chad and war-ravaged Sudan. Its other neighbors include Cameroon (whose Yaoundé airport I had a layover in), the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the Republic of Congo. Years are characterized not by four seasons but by drought and its opposite, the dry air blowing in from the Sahel from December through February, and the mango rains that welcome in March, offering respite. The red, red earth and the minerals running courses below it. In Bangui, when you head down the hill towards downtown, and the wide snake of the Ubangui river to your left, you will see the outline of the border with the DRC.

From 6 AM to 6 PM, the sun is up, and so are Central Africans. Early in the morning, the people rise and go about their days. Selling fruit at the market. Backing babies in pagnes (or long fabric strips) to work in their yakas (fields). The women fire up iron black pans, readying to fry makara (beignets) that they sell with coffee, their hands seemingly immune to the hot oil. Whether in the countryside, towns, or Bangui, one hears the morning calls of chickens and the hustle and bustle of those hoping to maximize their work output before the afternoon sun beats down and your clothes stick to your skin further.

Driving on the main road, one may catch a glimpse of a masked pale man riding on top of his vehicle, with a gun strapped to his chest. At the airport, researchers, uniformed Peruvian personnel from the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission, and NGO or project members move between locals coming back from Europe to visit family or in the other direction, towards France, Belgium, Canada, and the United States. Along the Ubangi River, the pirogues head out. Shirtless men dive deep under the water to collect sand, making pennies for profit. All around, there are women, and they are busy making do, working in offices, turning leaves into stew, beef into jerky, and garden vegetables into market profit.

Where Women’s Health Fits In

Herein, I use the physicality of Central African women to tell their stories, but the Black female body is not my concern. Broader sociopolitical realities are also at stake here, as well as Central African women’s right to intellectual personhood, artistry, their sisterhood, and things beyond love and reproduction.

Stories of women’s health in the Central African Republic are often told impersonally, through a series of vital statistics, ominous morbidity and mortality rates, or with a clear agenda-like aim. In this way, Central African women are not only nameless but they are stripped of their agency, purpose, and unique lifeways. They are monolithic to the colonial imagination. Congruently, the story of wars and conflict in the country is discussed largely within the lens of men, with women only featured as casualties, subjected to sexual violence, or raising families amidst displacement.

My original question for this project was: How are the actions of Wagner (or Africa Corps) mercenaries impacting women’s health outcomes in the Central African Republic?

However, the only paper I found that exactly wove that story was “Mortality beyond emergency threshold in a silent crisis– results from a population-based mortality survey in Ouaka prefecture, Central African Republic, 2020” by Robinson et. al. Otherwise, war and women’s health are spoken of as separate issues. That paper is further delved into in the End Here section. I begin this project with an essay about breastmilk and end with a transcript of my interview with Dr. Louisa Lombard, an anthropologist who does fieldwork in C.A.R., who spends more time discussing war with men up north than women.

In the aftermath of that interview and from conducting more extensive research, I saw it was worthless to piece out exactly how Africa Corps (by and of itself) is affecting things because one cannot separate the slew of conflict that has taken place since around 2013, and earlier. Instead, I found salience in the general theme of disenfrancment that is permeable to invasion of outside empires and forces.

I come from a biocultural background of investigating C.A.R through the lenses of animal and plant ecologies and Indigenous Ba’Aka health and lifeways. I now am curious about the health of all women (including Bilos, or non Ba’Aka) and the intricacies of war in the sense of:

How can life be made, despite this, or because one is a mother. Or, if the best way to survive these plagues (of colonization and competing empires) to band together in community, how is that realistically enacted in C.A.R.? How can I read war reports through a reproductive lens and reproductive research through a war and conflict lens?

Site Navigation

Originally, this website was meant to be viewed through the outline of the body, starting at a page entitled head and ending at the page entitled legs and feet. Guiding readers to explore the site that way seemed sensical, though readers are welcome to choose their own adventure. Additionally, I imagined the theme of war taking up a larger portion of the content.

In further iterations, I decided to format things a different way. I center reproductive sites and acts of the body such as lactation and childbirth, while weaving in histories of conflict, the interview, my personal travel photos and other’s journalistic photos within. I realized my limitations (the inauthenticity of writing about war when I’ve never experienced it), and have leaned into my strengths of reproductive biology, ethnography and story. Therefore, instead of starting with the head or a history lesson, I suggest you start by reading the lactation section. You’ll find your way through easiest that way. The weapons of French colonialism, Russian imperialism and mercenaries, and the overall harms of resource extraction and assaulting major ecologies are the main weapons here. In every drop of milk and the wet embrace of the air in Bangui as one steps off the plane.

Navigation bars can be located at the top of the main webpage, and at the bottom of every other page.

Glossary of sangho terms

- Bilo —> BaAka term for non-BaAka people

- budu—> amaranth greens

- cassava —> Manihot esculenta, a starchy tuber plant originating in South America (called yuca in Spanish and tapioca in Brazil) that is consumed widely in SubSaharan Africa.

- coli—> man/husband

- doli—> elephant

- gozo —>a staple carbohydrate food in C.A.R that is a “thick, doughlike…food made by boiling and pounding a starchy vegetable such as yam, plantain, or cassava (American Heritage Dictionary).” Also called fufu in West Africa

- kété —> small/young (depending on the context)

- koko —> Gnetum Africanum, a commonly eaten dark leafy green that is foraged from the forest

- kodro —> village

- kota —> large/older (depending on context)

- légé —> road

- makara —> beignets

- manioc –> another term for the cassava plant

- mundju –> foreigner, a term deriving from Bonjour

- MSF —> Médecins Sans Frontières or Doctors Without Borders

- Ndele —> Border (actually a Lingala word, one of the primary languages of the Democratic Republic of Congo)

- ndo –> place

- ndjundja —> referring to the leaves of the cassava plant, or a stew made of the leaves, meat, and peanut sauce

- nyama —> animal/meat

- pagne —> a long piece of African cloth used commonly as a wrap skirt or to back-carry babies

- Wa Na Wa —> Fire on Fire, or the name of the vodka brand created by Wagner in C.A.R

- wali —> woman/wife

- yaka —> agricultural fields