Introduction to the conflict

Anthropologist Dr. Louisa Lombard, whom I interviewed for this project (read that here), opens her 2021 piece “Sovereignty triangles Emotions and transactions in Central African relations with Russia” with pressing prose not about war in and of itself, but cinema.

Therein, she depicts the 2021 Russian propaganda film The Tourist that showcases the involvement of Russian fighters in C.A.R. conflicts between the president and armed rebel groups. In contrast to other film screenings that Dr. Lombard attended in Bangui, which took place at the Alliance Française where a few hundred people sat in rows of plastic chairs, The Tourist was premiered by tens of thousands of people at the “Chinese-built National Stadium” and was “glamorous.” Actors and directors walked out on a red carpet.

“The trailer for the 2021 Russian film The Tourist requires no language skills, its only sounds those of bloody, up-close battles: grunts, yells, screams, and the retort of automatic weapons (Lombard 2021).”

In my interview with her, I told Dr. Lombard about the visual evidence of Wagner I’d seen on my trip to C.A.R. in 2022, from roads torn up for extractive mining to masked men riding on tanks in the city, and the tall billboards advertising Wa Na Wa [Fire on Fire in Sangho] vodka. I attempted to verify the tales I had heard but had not witnessed firsthand. Was Wagner really stealing cassava from people’s fields to process into vodka? How widespread was the sexual assault of women and girls amongst fields of yams and cassava, the statistical truth to how Wagner is turning “their farms into rape centers (Philip Obaji Jr, 2024)?” And how directly was the Russian bombardment on Ukraine impacting Central Africa’s access to jet fuel and grain products from Ukraine?

A 2022 article from the Financial Times pieces together the story fragments swirling around me, where reporter Neil Munshi describes the “Voldemort quality to the Russian presence in the capital (Munshi, 2022) what with the hushed tone for which the word Russian is spoken throughout Bangui, contrasted with the sheer omnipresence of the mercenaries. Munshi observes the mercenaries all over the city: buying shawarma sandwiches at the Lebanese cafe, haggling with saleswomen at the artisanal market, drinking wine at a fancy restaurant. On the same day of the wine spotting, Munshi interviews “a woman who says she feared she might have HIV after being raped by three Russian fighters (Munshi, 2022).”

I also found evidence of violence at the site of C.A.R.’s mines, which I detail below.

Mining

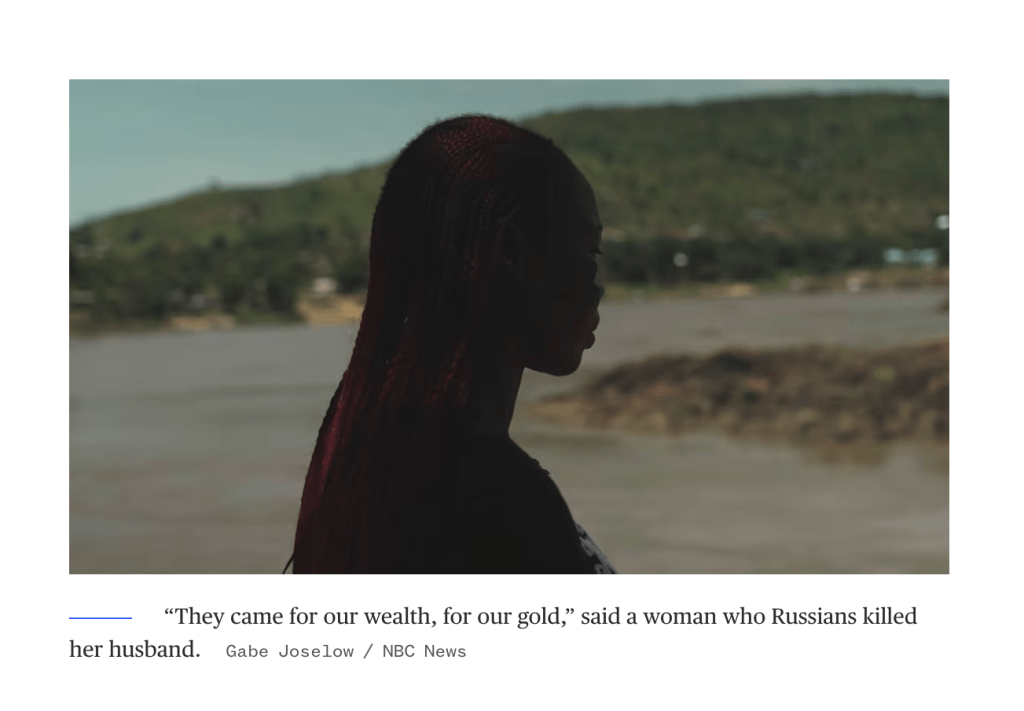

When I sought more current details on the situation with Wagner, news media proved to be a more reliable resource. A 2023 article from NBC titled “Russian mercenaries exploit a war-torn African nation as they lead Putin’s fight in Ukraine” discusses Wagner’s takeover of Ndassima, a gold mine north of Bangui that had previously been tended to by artisanal miners. The article features the story of a twenty-five-year-old woman (see image above) who told NBC her miner husband “had been working at the mine when he was ordered out by Russian fighters in the fall of 2021” and was shot to death for refusing to leave the mine.

Mine workers reported being raped by the Russians. Many others were beaten to death.While they had initially been told to join Wagner on behalf of embarking on anti-Séléka missions, the actual journey dissolved into darkness, and the men recounted killing many civilians. I am curious to know how the killings and degradations of miner men by Wagner impact the health of their wives and families, on the levels of displacement, income security, and the reproductive energetics of raising infants and young children without a partner.

Overall Displacement

Given all of the above, I was anticipating basing my entire project on the impact of Wagner on Central African women’s health. To look more holistically at the last 20-30 years of conflict in the country, as well as the brutal colonial legacy, seemed impossible. And yet, that is actually what Dr. Lombard called me to do.

SM: What are some major differences between how Wagner affects the country versus the former conflicts starting in 2013?

LL: Well, I don’t know if food security or health impacts are different now, although the level of intensity of armed violence is different. The fact is that ¼ of C.A.R.’s population is displaced at any given time. People live in their fields or villages. It is different depending on who is displaced, but this all affects food security. It is a political scandal that there is widespread hunger in the region. Humanitarian organizations will change food security guidelines to gain access to aid. This insecurity is an unnecessary tragedy upended by conflict. Policies are limiting access to foraging. There is overall uncertainty and displacement.

Being challenged this way has been disruptive. My grandmother spent her career as a market woman buying meat and produce wholesale and then selling it at the markets. She can still tell you the places to buy the best meat and so on and will point in the direction of which to procure them. This winter, my grandmother said there was a shortage of fish, somehow, in a city bordered by a river. If my people, the Yakoma, are fishing people who know rivers like roads, wasn’t there truth to that? And how else could I learn from Indigenous African epistemologies without falling into falseties that twisted reality into how I wish it to be? Where is my neat story about armed Russian men and Central African women’s bodies?

Still from The Tourist| IMDB

Roads as historical sites

All of these details felt conflicting. I needed information on contextualization, even if it was less recent. One thing I found for that was “Na lege ti guiriri (On the Road of History): Mapping Out the Past and Present in M’Bres Region, Central African Republic” by Dr. Tamara Giles-Vernick (1996), which examines spatial-time constructions of history among the Banda ethnic group in C.A.R. Dr. Giles-Vernick found that Banda history-tellers utilized “images of roads (lege) and places (ndo) to express their connections to past people, practices, knowledge, spaces, and an idealized social order (Giles-Vernick, 1996).”

Rather than providing a temporal sequence of past events, Banda people of the M’Bres region in the Central African Republic expressed guiriri, or “history,” as a spatial-temporal phenomenon.1 They explicitly linked it with lege (road) and ndo (place)…Banda people with whom I spoke translated guiriri into the French histoire, using the term severally as a “past space,” as particular knowledge, practices, and people associated with this past space, or as “proper” social relations. Similarly, lege could be translated as “road,” but also as “way” or “path,” and ndo connoted both a physical space and a position in a social hierarchy

Giles-Vernick, T. (1996). Na lege ti guiriri (On the Road of History): Mapping out the past and Present in M’Bres Region, Central African Republic. Ethnohistory, 43(2), 245. https://doi.org/10.2307/483397

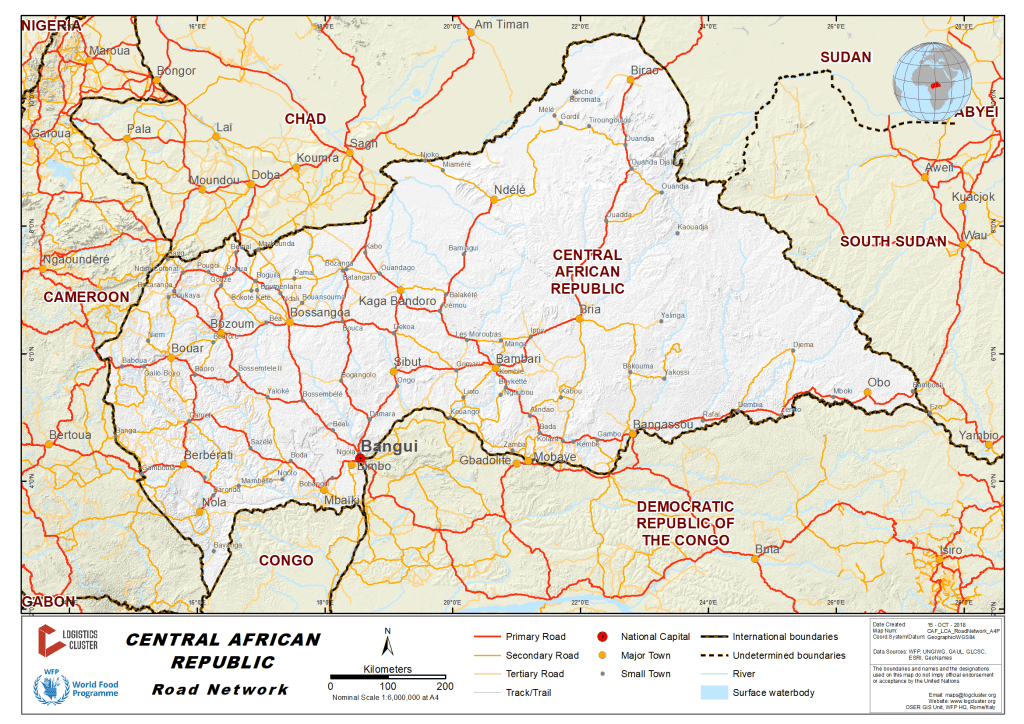

The familiarity of those Sangho words helped root me into a part of the discussion I had neglected. The road is so much of the story within a place marked by dry and wet, hot baking sun and tire-sinking mud. Roads in Central Africa tell the story of colonization, not just weather patterns. Stories of better times in the country are marked by newer cars, buses, taxis, and trains. In 2022, when our jet fuel failed to materialize, the 302-kilometer drive from Bayanga to Bangui took twenty-three hours. My parents recounted that twenty years ago, it only took about eight. Not only is Wagner tearing up the roads and forcing us to divert to safer yet slower routes, but the years marching on since the French occupation and a more organized C.A.R., since things were shiny and new. These stories have shown me, as Dr. Giles-Vernick found, that roads in Central Africa are a site upon which “women and men, seniors and juniors, and teachers and learners made conflicting claims about authority and access to resources.”

Road Safety Narratives

Now with this lens of roads fresh in my mind, I became more attuned to mentions of them. While reading a report from Logistics Cluster (a branch of the ISAC), I spotted a comment about the Travel Time Matrix of C.A.R: “Not available – it depends on the dry and wet season; rainy season is from May to November. Travel time depends also on the availability of MINUSCA [United Nations Multidimensional Peacekeeping Mission] escorts.”

Meanwhile, in “Sovereignty Triangles,” Dr. Lombard challenges MINUSCA for double speak. Despite being the longest-lasting peacekeeping mission in C.A.R, at UN Meetings in 2018 and 2019, “MINUSCA officials claimed that the Russian presence in the CAR was so minimal that it was silly to focus any attention on it (Lombard 2022).” Fast forward to 2022, when MINUSCA officials were blocked by Central African and Russian officials, sometimes by gunpoint, and the thousands of MINUSCA missionaries remaining are left with little ability to do anything of impact. And yes, as it turns out, the exorbitant pricing of food and lack of grain products in C.A.R. is not all in my grandmother’s head, as it is recounted as such in Lombard’s piece. Yet her consistent pointing towards overall histories of displacement, coupled with Banda epistemologies and my family’s stories, still leave me wondering. The story is ultimately confusing, ever-unfolding, and nonetheless important.

Conclusion

As explained earlier, I hypothesized that Wagner is negatively impacting Central African women’s health seems correct, but one cannot state that without linking to the longer history of ongoing conflict and displacement in the country, causing widespread food insecurity, sexual assault, and so on. As stated above, I am curious to know how the killings and degradations of miners by Wagner impact the health of their wives and families. And linking back to the Banda epistemologies, I seek further insight in how difficult it is to retell the history of one’s country by its roads when the roads themselves are being gutted by the hitmen of a foreign empire (Russia) competing against the actions of another empire (France) who still demand you bow to their feet.

I’ve gathered the story’s fragments when linking conflict, colonization, and women’s bodies in Central Africa. News media about Wagner. Midwifery papers about Bangui Community Hospital in French. Collecting the complete reproductive histories of three Ba’Aka women that summer of 2022. Roe v. Wade was freshly overturned in the states, but we ate fried fish cross-legged under the wooden tourist lodge. I have tales of drivers getting roadside IVs and the dangerous bustle of the mining town of Boda. I know how little girls bathe outdoors behind the clothesline curtain of their homes. I know the tight pulling of my scalp as my hair is braided, the feeling of crossing a checkpoint, the uncanny sight of spotting Ben and Jerry’s at the Lebanese grocery store, and the ominous presence of a white man in a mask.

Continue on the kété légé (small road) with me, as we journey to another site of conflict and the body, reproductive health, and the Womb.