to be born or to give birth [in the Central African Republic] is to take a risk MSF (Médecins sans frontières)

To this fractured geography, add war. More than a decade of violence has killed and injured droves of civilians and driven more than 1.4 million people from their homes — a quarter of the country of roughly 6 million. Without stability, hospitals and schools can hardly function, crops can’t be harvested, and roads fall apart. Women give birth without health care, or light at night (Amy Maxmen, Undark).”

Introduction

Herein, I seek to understand how themes of war, conflict, and displacement weave into Central African women’s experiences with childbearing, proving that obstetrical narratives, whether they be in a list of statistics, in peer-reviewed data, or news articles, are not as neat and blameless as they initially appear.

During my research for this section, I read through several midwifery papers in French by scholars and medical providers at La Maternité Communautaire de Bangui. I also learned about the Wakobo ti Kodro project through the Alima NGO, which equips village or lay midwives with tablets to assist their process of tracking patients through the antenatal and birthing periods.

Further, I referenced my research. In 2022, during a family vacation to C.A.R., my mother and I interviewed three of her Ba’Aka grandmother friends in Bayanga about their reproductive histories and the stories of each of their lives and stillbirths. One of the women’s stories can be read here. Finally, I relied on accounts from family about the inner workings of Bangui hospitals,

Basic statistics of outcomes

There are 15 gynecologists in the Central African Republic. How they can serve a country of 5.152 million doesn’t remain to be seen, as the impossibilities have already been demonstrated. According to 2015 data from UNICEF, C.A.R. holds a Maternal Mortality Ratio of 882 deaths per 100,000 live births. For every 1,000 births, 34 babies will be stillborn, and 13 babies will be born preterm for every 100 births. (Maternal and Newborn Health Disparities Central African Republic).

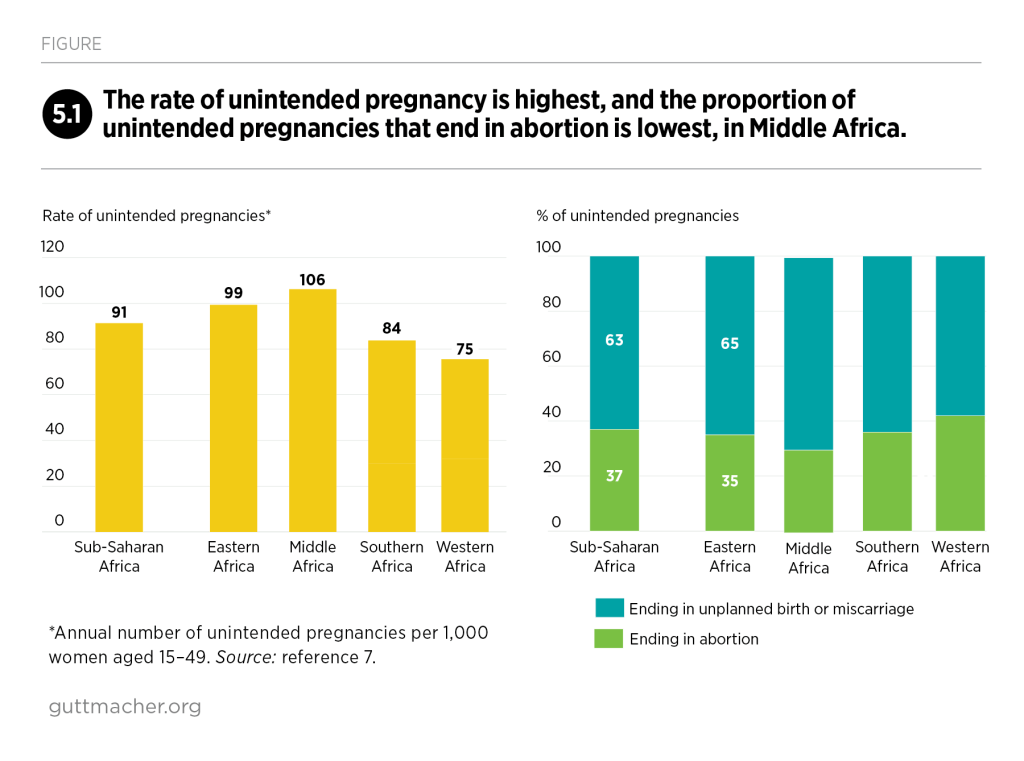

ABORTION

As it happens, maternal birth complications in C.A.R. often result from a mother’s previous history of clandestine and unsafe abortion. Abortion in C.A.R. is illegal unless a pregnancy is the result of rape. A 2020 study by Ngbale et. al. discusses this. Firstly, in C.A.R, “voluntary termination of pregnancy is prohibited by law (article 190 of the Central African Republic Penal Code) (Ngbale et. al, 2020, 745).” The researchers used the site of Bangui’s main maternity hospital to investigate the complications resulting from clandestine abortion. Factors associated with having a clandestine abortion (CA) were being between 20 and 24 years old, having 2.6 children, and being a student. Nearly 80% of cases suffered from infectious complications. Around 40% of cases required Laparotomy, an abdominal surgery. 12.7% of the women died, most of them at a gestational age of 12 weeks or more. Of the people the women sought to cause their abortions, 29.2% of them were labeled as “unqualified health workers (Ngbale et. al., 748), which increases the risk of sepsis due to non-sterile conditions.

Another study, “Clandestine Abortions and Its Complications at the University Hospital Center of the Sino-Central African Friendship” by Roch M’Betid-Degana et. al, 2023 discussed how women attempted to end their pregnancies. Out of a sample of 254 women, only 32% used the medicinal or Misoprostol method, something considered among the gold standard of abortion care. This suggests access to Misoprostol is extremely limited in C.A.R. 18% of women used a traditional method, which is not made clear, but I assume likely entails herbal ingestion. Finally, 50% of women used a mechanical method, which the authors tease out as “the dilation of the cervix by the cassava stem, the Hegar candles, the probes which are infusion tubing cut and introduced into the cervix, 2 cases had fled at the level of the uterine muscles and emerged on the skin at the pubis part two years later (1608).” Some complications listed include perforation and pelvic inflammatory disease, two things that can certainly make a future full-term childbirth risky due to their wearing impact on the uterus.

Hospital Birth in Bangui

I will now consider a 2023 paper by Mina Blaise Amory et. al., whose French title translates to “Actions of Midwives to prevent Hemorrhage during Immediate Postpartum within the maternity of L’Hôpital Communautaire de Bangui.” Data was collected in this paper by observing and surveying midwives at the community hospital.

According to the paper, which features a series of demographic statistics, the average midwife at the hospital is 44 years old, with all the midwives between the ages of 30 and 51. Thereafter, the authors cite instances where some or all of the midwives did not list or perform actions that their epistemology deemed necessary. These initially are, as follows, not listing temperature as a constant to monitor, two midwives not mentioning the texture and tone of the uterus, and failure to perform a speculum examination. In Table VI: Distribution of activities relating to hygiene care for women in labour, the authors drill home their concerns of cleanliness, with their standout statistic being “nearly half of midwives did not wash their hands before providing care.” First, I wish to pull apart that statistic, with the stories of Bangui hospitals of which I heard growing up, which relates to the general trend in unstable utility access.

As I have been told growing up, Bangui hospitals are dark environments, with little sunlight or windows. Random puddles on the floor are common, their source is completely questionable. Relatives of the invalid are given a prescription script and then must source the medications and equipment (such as a needle) their relative needs, from somewhere else. Furthermore, the invalid’s family must pay for this medication and equipment separately from the hospital bill. Put another way, if someone’s family cannot afford those resources, they must either resort to buying a different and cheaper medication, or their relative is forced to endure the procedure without adequate pain relief. Unlike a U.S. hospital that boasts a kitchen and food service industry within the building, Bangui families cook meals outside the hospital on cook fires, and bring them to their family member(s). During the peak AIDs crisis in C.A.R., dentists were avoided for fear of contaminated materials.

Yet, the above images of an MSF (Médicins Sans Frontières) supported neonatal unit tell a different story, one of cautious hope and resilience. A 2023 article about the center, “Being Born Safe: New Maternity Clinic opened in Central African Republic,” features photos of mothers holding newborns that wouldn’t have survived had it not been for the capability of the medical center. In one photo, a fifteen-year-old mother proudly holds her baby, born at 36 weeks (4 weeks early), who was cared for in the intensive unit. Another photo, the one I included above, features “Stephanie Kamangomda with her son Archange, born prematurely at 28 weeks and who spent 45 days in the intensive care unit at CHUC. The medical teams nicknamed Archange “the general” because of his fighting spirit.”

Water Insecurity as a Disparity-Causer

So, how do we make sense of these competing narratives? One of ultimate despair as told by news media, another of hope and resilience spurred on by foreign projects and NGOs, and lastly, how Bangui’s unprecedentedly burdened (yet still) existing healthcare infrastructure is widely critiqued in the literature. For instance, Amory et. al chastise Bangui’s midwives for not wearing sterile gloves or an apron during care, for neglecting to use a speculum (explore that further in Colonial Gynecology), clean patients’ vulvas, or clean the birthing table. The untrained eye may immediately run to shame and blame, or assume that the midwives weren’t properly trained.

Note how all that requires water. In C.A.R., water, running from the taps, is a highly unstable resource. According to 2022 data from the Global Water Programme, “barely 30 percent of the [Central African] population has access to drinking water.” More closely, drinking water access is observed in 27% of people in rural areas and 36% of people in Bangui.

Bangui’s water supply infrastructure is archaic and poorly

maintained. Even at full capacity, it falls short of demand. Water

supply systems are limited to Bangui and a few major towns.

Most rural households use wells with hand-operated pumps.

CAR has no integrated sanitation system combining sewerage

networks and wastewater treatment. Most urban households

have private latrines; however, this is not the case in rural

areas, where open defecation is prevalent, with environmental

and public health risk implications (African Development Bank,

2017).

For example, during my family trip to C.A.R. in 2022, we stayed in a compound while in Bangui. Despite that, water and electricity were not constant there. I became hyperaware of uneven resource allocation in our world, how in America and other high-income countries, we generally expect our homes’ taps to run, our lights to glow, and our WIFI to load in mere seconds, as long as we have paid the utility bills. The increases of natural disasters due to climate change have given us a greater understanding of our deep reliance on water and power units. Still, the impact of environmental and institutional disaster remains skewed and uneven, so that many people have little concept of what it is to boil all one’s water and light candles for days. In the United States, we certainly do not expect our hospitals and other public institutions to be without running water, kitchens, equipment, and medications. And yet, in a country where gold, diamonds, and other rare minerals rest right underneath the soil, but there are only three ventilators for the five million people within its borders (Norwegian Refugee Council), such is the case.

For further themes of colonization and how it intersects with gynecology: