On the Biopolitics of Demographic Control in French Central Africa

Speculums

As mentioned on the previous page, Central African hospital midwives were chastised in the literature for not using speculums on laboring women. I had never heard of speculums being used on laboring and freshly postpartum women. It seemed medieval!

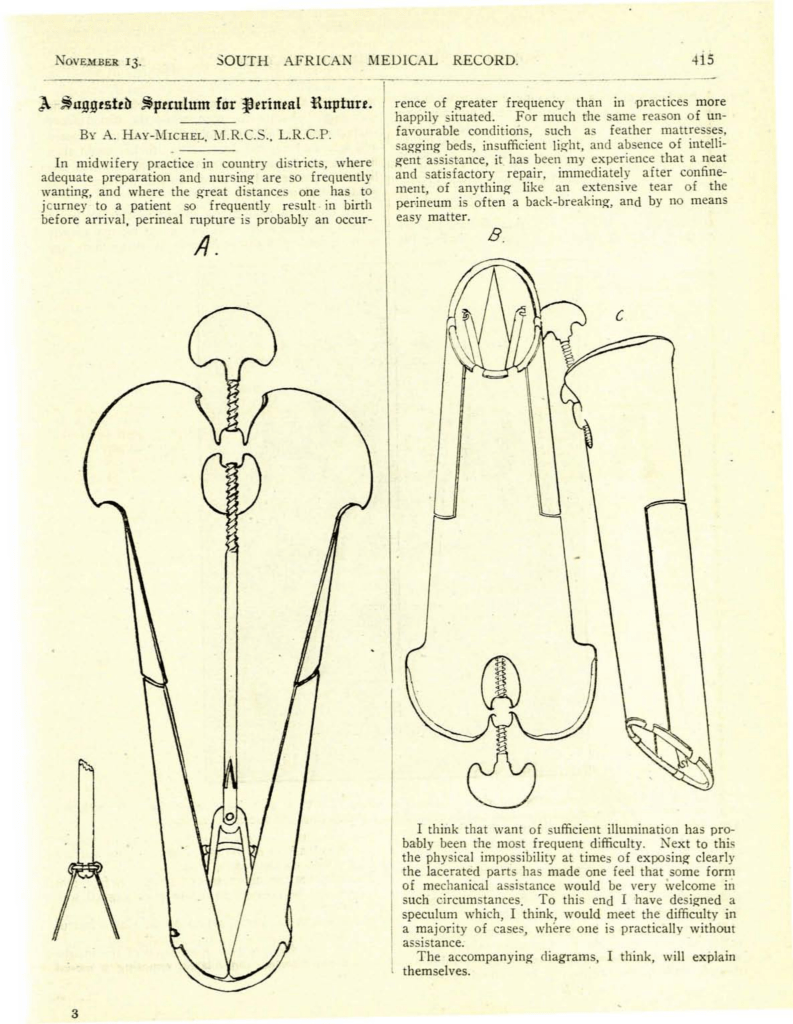

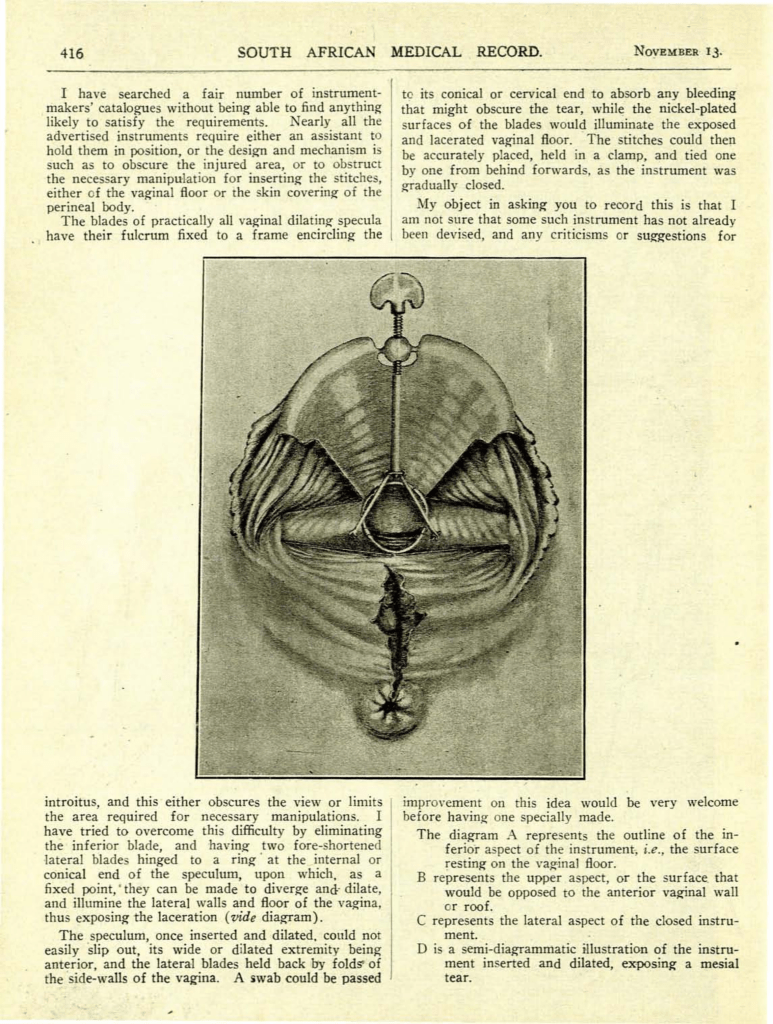

I researched the usage of speculums in childbirth and came up with little. I did find an old publication in the The South African Medical Record entitled “A suggested speculum for perineal rupture” by A. Hay Michel, M.R.C.S., LRCP (Nov. 13th, 1920). A comparison to J. Marion Sims (the white male obstetrician who invented the speculum through abusive procedures on enslaved women experiencing fistulas) is warranted, but I first see other connections.

Looking closer at the laceration in the vide diagram on the second image, it is evident that A. Hay Michel advocated for speculums to repair perineal tears after childbirth. Still, inserting a speculum into such a recently postpartum woman is barbaric. Therefore, the chastising of Central African midwives for not having access to speculums feels like another extension of the colonial empire’s viewpoints on women’s bodies, their deservingness (or lack thereof) of agency, and obstetric consent.

Nancy Rose Hunt: “Colonial MedAnth and the Making of the Central African Infertility Belt”

In “Colonial Medical Anthropology and the making of the Central African infertility belt”, Nancy Rose Hunt (2007) explains that throughout “equatorial Africa in the interwar and postwar periods…Belgian and French colonial officials, missionaries, and doctors worried about the psychological consequences of colonialism on birth rates and the fecundity of women (Hunt, 2007).” Hunt describes how the colonial imagination viewed these ‘colonial anxieties’ of race suicide, degeneration, sterility, and extinction. To the colonizer’s mind, low fertility and spontaneous abortion (miscarriage) in African women was a consciously willed phenomenon as well as “a psychological or neurasthenic one related to the [shell] shock of life under colonialism.

She goes on to describe the work of Belgian colonial doctors in 1930s Zaire (Democratic Republic of Congo) on issues of STDs among women, and their usage of penicillin to treat the issue immeaditly after the drug became available. The Belgian doctors, among them Dr. Robert Allard, believed that STDs (such as gonnorhea) contributed to a low birth rate among the Mongo ethnic group. In addition to performing gynecological examinations, surgeries, and providing antibiotics, Dr. Allard modified a psychological test to test “Mongo women’s desire for modernity as a possible sterility-producing psychological factor,” wherein he showed them a series of images, half of which he believed would indicate a desire for maternity (household objects, mother with children, and a mother breastfeeding) and half a desire for sterility (woman drinking beer, an evolved man doing nontraditional work, and a bicycle).

“Allard’s findings led him to conclude that psychosomatic dynamics, especially ‘the wish for modernist emancipation from the responsibilities of maternity, at least among young subjects’, played a role in Mongo infertility.”

Along with this theme of Belgian colonial medicine, I am further struck by this image of a milk depot and baby clinic from “Medicine and Colonialism.” The Congolese women wrapped in pagnes holding their tiny babies and toddlers, the stark white of the nun-nurses, the sterility of their gaze. And the baby lying on the scale, seemingly hypnotic. A sense of fear. No one in this image appears happy, pious, or at ease. The article goes on to reference Nancy Hunt below.

Figure 3.2 Leopoldville. Milk depot and baby clinic, n.d. From “Medicine and colonialism” (2021)

“As Nancy Hunt also reveals in her study of the Congo, a nuanced cultural history can be reconstructed from examining anxieties surrounding what are, in the West, squarely medical topics such as depopulation and infertility, through examination of ‘therapeutic insurgency’ from the Congolese as a response to a repressive biopolitics imposed by a ‘nervous state’. “Medicine and colonialism” (2021)

Bringing it all Together

Much of Dr. Hunt’s work concerns health activist efforts and regimes in the effort against AIDs in Francophone Central Africa, as well as the history of STD panic in the region. How does this relate to current-day academics chastising Bangui community hospital midwives for not using speculums on laboring women or practicing a pristine performance of hygiene in a low-lit, systemically under-resourced environment on systemically under-resourced bodies? It relates because what has been consistently gone unmarked here are Central African/Congolese women themselves, their (as discussed on the Womb page), deservingness for obstetric consent, agency, and overall decency. Behind campaigns advocating for condom usage, or colonial doctors testing Congolese women’s desire to produce children, is a desire to funnel attention away from the simplest answer. What would happen if we asked Central African women why they cannot conceive or if they wish to conceive at all?

“Mothers of Gynecology” Sculpture| Bloomberg

A quarter of the Central African population is displaced due to conflict and most people do not have access to clean water or food security, or the ability to complete more than six years of education. It is no wonder that epidemiological data (such as Robinson et. al, 2021) have found C.A.R.’s birth rate as lower than the death rate (read more about this paper on end here). The design of the colonial empire is to ensure that the native population is an obedient, never-ending source of labor. Then why is it confusing to the colonial imagination that this results in sterility, or women’s desire for reproductive agency? Looking at it this way, we are centering the biopolitics of the nervous state, which produces nervous system results. Therefore, the colonial idea that Central African midwives should use on their kinswomen the same tool that J. Marion Sims invented after brutally experimenting on enslaved African-American women in the American South is not surprising at all.