Perhaps in the imaginations of many, lactation in the Central African Republic is a site left relatively undisturbed. Surely, mothers are exclusively breastfeeding their children for months on end, since the water available is not suitable for sensitive infant stomachs. How would anyone afford formula or an abundance of complementary foods anyway?

And yet, perhaps surprisingly, for those who haven’t considered the concept of yearning towards modernity, and the sheer necessity to feed an infant, the actual data proves otherwise. I will explore how lactation in the Central African Republic is affected by war, food insecurity, and displacement.

First, let’s review the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations surrounding lactation:

WHO and UNICEF recommend that children initiate breastfeeding within the first hour of birth and be exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months of life, meaning no other foods or liquids are provided, including water.

Infants should be breastfed on demand – that is, as often as the child wants, day and night. No bottles, teats, or pacifiers should be used.

From the age of 6 months, children should begin eating safe and adequate complementary foods while continuing to breastfeed for up to two years of age or beyond.” WHO Breastfeeding Recommendations (source)

In actuality, the WHO acknowledges that its goals have not been met. Worldwide, less than half of babies under 6 months old are exclusively breastfed (EBF).

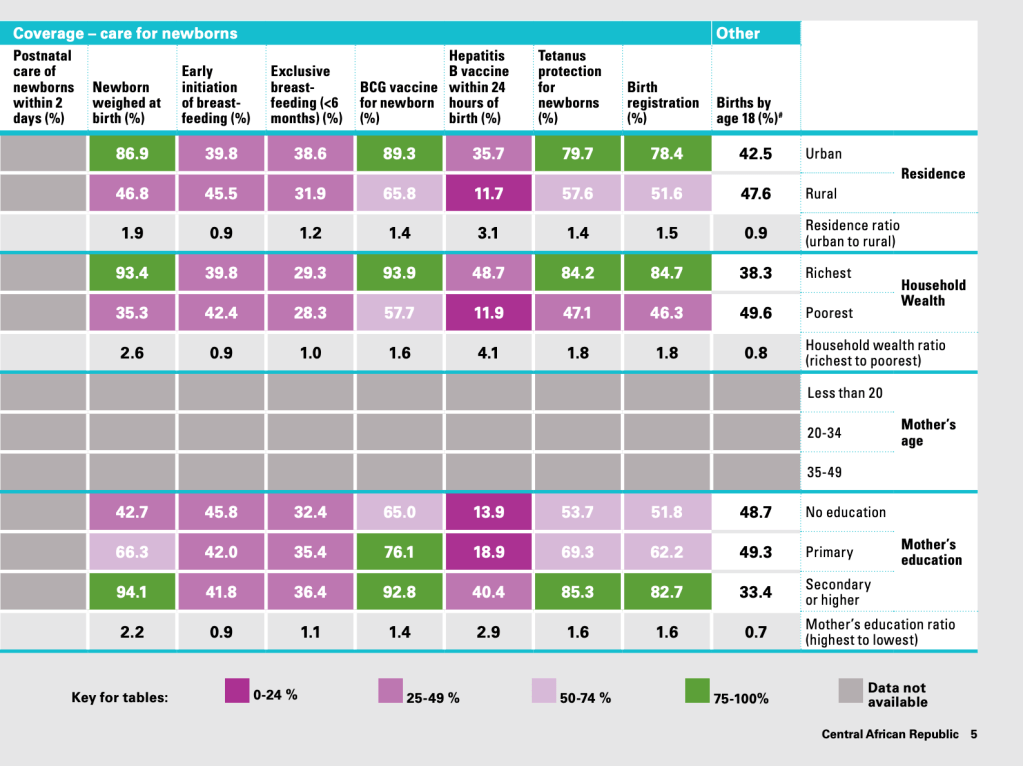

Next, I will review the 2015 Maternal and Newborn Health Disparities Report on the Central African Republic, which provides good data factoring in the participants’ residence, household wealth, and education level. A small summary is provided herein. You can also view the data within the study’s data table (see image below).

Residence

Regarding residence, it is reported that amongst urban mothers, 39.8% practice early initiation of breastfeeding, and 38.6% are EBF before a baby reaches six months. Comparing rural mothers, 45.5% initiated breastfeeding early, and 31.9% of mothers exclusively breastfed their baby before they were six months old.

Household Wealth

When analyzing mothers with the variable of household wealth, the data shows that poorer mothers are initiating breastfeeding more so than richer mothers (42.4% vs. 39.8%), but are EBF slightly less than their wealthier counterparts before their baby reaches six months (28.3% compared to 29.3% of mothers at a higher socioeconomic level).

Education Level

Finally, in an examination of mothers by education level, within the categories of “no education”, “primary”, and “secondary or higher”, it appears that mothers with no education have the highest rate of early initiation of breastfeeding (45.8% compared to 42.0% for primary and 41.8% for secondary or higher). However, when it comes to which mothers are still exclusively breastfeeding before the baby reaches six months of age, those who had received a secondary level of education or higher came in first at 36.4% (compared to 35.4% for primary and 32.4% for no education).

Contextualizing

At first glance, the 2015 data is confusing. How could it possibly be true that urban, richer, and more highly educated mothers in C.A.R. begin by having a lower rate of breastfeeding initiation in comparison to their rural, poorer, and less educated counterparts, but then end up having a higher rate of exclusive breastfeeding the first six months postpartum? Is there any overlap between the variables?

A comparison to a country of similar status feels apt. Coincidentally, the country with the highest rate of EBF in the world is Rwanda (80.9% of infants breastfed for the first six months), according to 2025 data from the World Population Review. Comparatively, C.A.R. is given a percentage of 36.2% for the same statistic, and the United States, which falls behind on most maternal and child health goals before you even compare amongst racial groups, is at 25.8%.

But why Rwanda, in comparison to other countries with strong breastfeeding cultures? Were there lactation campaigns post genocide? Or is it something to do with President Kagame using dignity politics to ban secondhand clothing imports and strongly encouraging anyone from entering the capital city of Kigali if they don’t have shoes? Generally, is corruption inflating Rwanda’s breastfeeding rate numbers?

As it seems, breastfeeding isn’t the only indicator of maternal and child success. For instance, a 2023 study published in the Rwanda Journal of Medicine and Health Sciences found that “47% of rural children and 27% of urban children are stunted, which could be linked to poor exclusive breastfeeding (Nyirahirwa et al., 2023).” This theme, of reproductive practices that are assumed to be always beneficial and never beneficially negligible, will become more apparent later in this essay.

Mother’s Health Status And Breastmilk Biomes

More Central African data further cements that lactation is not ultimately beneficial, but its benefits are environmentally dependent. Food insecurity causes more than low body weight and kwashiorkor. It affects a mother’s breastmilk, too. Such is determined in “Food Insecurity and Maternal Diet Influence Human Milk Composition between the Infant’s Birth and 6 Months after Birth in Central-Africa” by Jeanne H. Bottin et. al. (2022). In the study, 48 mothers in Bangui were surveyed according to their diet and birth outcomes, and their breastmilk was sent to a European lab for analysis.

The authors stated that “at delivery, 16 of the 46 (34.8%) women with a blood test were undernourished (which was defined by albumin plasma levels <35 g/Lz) (Bottin et. al, 2022).” Similarly, 43.5% of mothers were found to be iron-deficient, which the study reports is not far off from other African and WHO estimates. Mothers were also deficient in vitamins A, C, and E.

At first glance, being somewhat emic to C.A.R, I understood that the average Central African may not be eating meat every day. Yet it seemed insane that women living in a culture that consumes dark leafy greens every day, and being in a tropical area where fruit is available year-round, could be deficient in those vitamins.

PARASITE EFFECT

Then I was reminded that, given the profound density of parasitic organisms in C.A.R., most citizens will likely become subject to them at some point in their lifespan, despite extreme hygienic efforts around bathing, cooking, and house cleanliness. And indeed, parasites are known to deplete the body’s nutrient stores. According to a 2003 paper in the Journal of Nutrition:

“In the developing world, young women, pregnant women, and their infants and children frequently experience a cycle where undernutrition (macronutrient and micronutrient) and repeated infection, including parasitic infections, lead to adverse consequences that can continue from one generation to the next. (Steketee Richard W. 2003).” Therefore, Central African women may require more nutrient-dense foods to offset the parasitic depletion effect.

NUTRIENT NEEDS

Beyond needing to supplement more to navigate potential parasites, we know that women’s micronutrient needs increase significantly during pregnancy and insurmountably so during lactation. I learned as such from “Minerals in Pregnancy and Lactation: A Review Article (Khayat et. al, 2017), which has a handy table of recommended micronutrient needs for women at various ages and reproductive life stages. According to the chart, teenagers and women aged 14-50 generally should intake 8-18 mg of iron daily. During pregnancy, this need increases to 27 mg a day. Non-pregnant and pregnant women should intake 1000 mg of calcium per day. During lactation, they require up to 1200 mg per day. Finally, selenium (Vitamin E, essentially) needs increase from 55 mg in non-pregnancy to 60 and 70 mcg/day in pregnancy and lactation, respectively.

Therefore, it is easy to see how a Central African woman, from leading an extremely active lifestyle (walking everywhere, chopping wood, doing fieldwork, grinding manioc, hand washing clothes, carrying babies and baskets), may be burning more calories than she consumes. Moreover, she may be consuming a diet low in variety, due to poverty, displacement, climate change-related crop blights, or the disruption of Wagner on C.A.R’s food economy. Depletion during the metabolic marathon of her childbearing years is likely.

BOTTIN: MATERNAL DIET

In the Bottin 2022 study, women ate three meals per day on average. Women were found to have eaten fewer meals in the week following childbirth than in the follow-ups at weeks 4, 11, and 25 postpartum. The maternal diet was described as monotonous, consisting of the following:

- Grains, cassava white tubers (base of diet)

- Meat, poultry, and fish (dried meat, dried fish, and chicken)

- Condiments (bouillon cubes, tomato paste, and chili peppers)

- Other vegetables (okra, onion, and tomato)

- Dark leafy greens (consumption significantly increased in the first 6 months postpartum)

- Sweet foods (biscuits, makara or beignets).

- Eggs (rarely consumed)

Fascinatingly, compared to women not shown to be malnourished at the point of delivery, the undernourished women consumed more dark leafy greens than women who were more nourished. This was salient according to the twenty-four-hour diet recall and the food consumption questionnaire. Moreover, undernourished women were shown to have a greater consumption of “other foods” like instant coffee, and undefined foods (which I can imagine are perhaps peanuts and sugar cane, little things for quick energy). Finally, “the twenty-four-hour recalls displayed a significantly higher consumption of red-palm oil and sweet beverages among the undernourished women at delivery, compared to the non-undernourished mothers,” who were shown to consume more powdered milk and dairy at the point of delivery.

MILK DIFFERENCES

As I previously stated, the Bottin study sent breastmilk samples from the women to a European lab for analysis. Among the groups of women labeled undernourished and those labeled as nourished, differences in HM (human milk) were observed. The HM of women facing food insecurity was associated with lower levels of free amino acids, total fatty acids, retinol (Vitamin A), and Omega 3 PUFAs. In other words, their milk lacked essential building blocks for infant well-being and growth.

In the discussion, Bottin et. al. note that “even in the context of extended food insecurity in our cohort, high household food insecurity levels were significantly associated with reduced levels of” everything I described above. “This is particularly worrisome as the ‘breastfeeding paradox’ shows that the households with an increased risk of food insecurity tend to reduce breastfeeding in quantity and duration in Western and African countries (Bottin 16).” Bottin’s teasing out of this breastfeeding paradox reminds me of the concept of total motherhood from Dr. Joan B. Wolf, which is described below.

TOTAL MOTHERHOOD

In Against Health, an assigned book in ANTH 340, there is a chapter entitled “Against Breastfeeding”, Dr. Wolf (a women and gender studies professor at Texas A&M University), discusses “total motherhood” which will be useful in our understanding of the tradeoffs Central African women make while nursing their infants.

Dr. Wolf makes the case that breastfeeding’s benefits have been inflated, or that no matter how one spins it, “breastfeeding is not free” and that “maternal labor is understood to be natural and therefore without cost (88).” Wolf describes how society deems the responsibility of ensuring an infant’s safety, normal development, and life stage optimization solely to mothers rather than any other caregiver. She later exemplifies how the National Breastfeeding Awareness Campaign (NBAC) “tried explicitly to connect with African American and working-class women, whose breastfeeding rates are well below those of white and Hispanic women,” yet “did not take seriously the costs of breastfeeding for Black and lower-income women. Like *total motherhood, the message of the campaign was decidedly white and middle-class (89).”

*total motherhood

- moral code, “a moral mother will subjugate herself completely to a socially defined, all-inclusive notion of the needs of children.”

- “Good mothers themselves have no needs, repress their wants, and behave in ways that reduce..risks to their children, regardless of the costs to themselves.”

Does total motherhood add to the sheer physiological reality of motherhood as costly yet unavoidable tradeoffs that Central African mothers make? As has been demonstrated, to gestate a child to term, deliver them, and nurse them is extremely costly for any woman, especially for those who begin the childbearing year in a nutrient-depleted or parasite-ridden state. Moreover, as the data demonstrated, human milk composition will shift negatively to reflect gaps in the maternal diet. Wolf’s chapter mainly focuses on the North American (or high-income country) context. Yet her focus on how breastfeeding campaigns target Black mothers is relevant here. We can apply her analysis here to tease out the expectations placed upon African women that so often ignore the constraints that post-colonial reality and their own cultures place upon them. That work is beyond this project’s scope and may have already been done, but is nevertheless needed.

Conclusion

Ideals surrounding how mothers should feed their babies are made evident by most global health projects and maternal and child health campaigns. What is less often considered are the roles of conflict and war, changing economic structures, ideas of modernity, and survival-hood on mothers’ actual capability to feed their infants. Also, what isn’t troubled out in the 2015 Maternal and Newborn Health Disparities report is the sheer level of displacement Central Africans were experiencing in those years, and how that would affect the ability to produce sufficient breastmilk. Further, how beneficial is a lactation campaign when the breastmilk isn’t nutritionally complete?Because of this, the “breastfeeding paradox” and “total motherhood” are useful terms for contextualizing these constraints. The solution, if there could be one, is not lactavism but somehow, dramatically increasing levels of food security in the country. That, of course, would demand an end to the major aspects of conflict, war, and displacement present in the country.

Read on to the next page, Roads of Conflict, to explore themes of how war constrains women’s choices further.